I have an essay in the new issue of Onsite Review. It is about witnessing, forensics, and the status of speech today. You can read it in Onsite, get an online subscription to the magazine, or read a version of the essay below the fold.

I.

In the spring of 1960, Mossad was in Buenos Aires planning the abduction of Adolf Eichmann, when it heard that Josef Mengele was in town. The agents running the operation didn’t want to jeopardise it by taking on another target: Eichmann was captured and Mengele slipped away; his remains were exhumed in 1985. In Mengele’s Skull: The Advent of a Forensic Aesthetics, Eyal Weizman and Thomas Keenan claim that Eichmann’s capture and subsequent trial inaugurates the ‘era of the witness’, in which giving testimony against the excesses of state power becomes a central feature of political life. In contrast, the analysis of Mengele’s skull, carried out in the 1980s, heralds the rise of a political emphasis on material objects and their forenisc analysis. As the figure of the witness loses authority in the 21st century, it is forensics—in architecture as much as in archaeology—that will increasingly take centre stage, legally and politically. It is not man that will testify, but his ruins.

II.

At Eichmann’s trial, the testimony of survivors was valourised not just as evidence, but for its own sake. In the aftermath of a Nazi regime that didn’t just attempt to destroy the Jewish people, but also to destroy any evidence of the destruction, the very existence of survivor’s testimonies was itself politically important.

With the beginning of the 1990s, however, human rights organisations began gaining visibility, as ‘the international community’—that motley crew—began to search for new justifications in which to house post cold war foreign policy. Witnesses began to testify at ad hoc international tribunals—for former Yugoslavia from 1993, for Rwanda from 1994—and their testimonies were recruited as justifications for military and humanitarian interventions. Witnessing was no longer an ethical end, but increasingly the prelude to political action.

III.

These days I spend hours going through the material coming out of Syria. Competing claims and endless YouTube videos. Everyone is a (potential) witness, even if what is witnessed is unclear. The witness of the second half of the 20th century was marked by a distance: someone survived, and brought back testimony. This distance is gone; the witness doesn’t live to tell the tale—he tweets it immediately.

The figure of the witness is now pluralised and immediate; its sanctity is eroded. The era in which the witness was valourised as a subject (for taking the risk; for surviving) has turned into an age in which the witness is nothing more than his subject position. The line between propaganda and witnessing is today incredibly hard to draw.

IV.

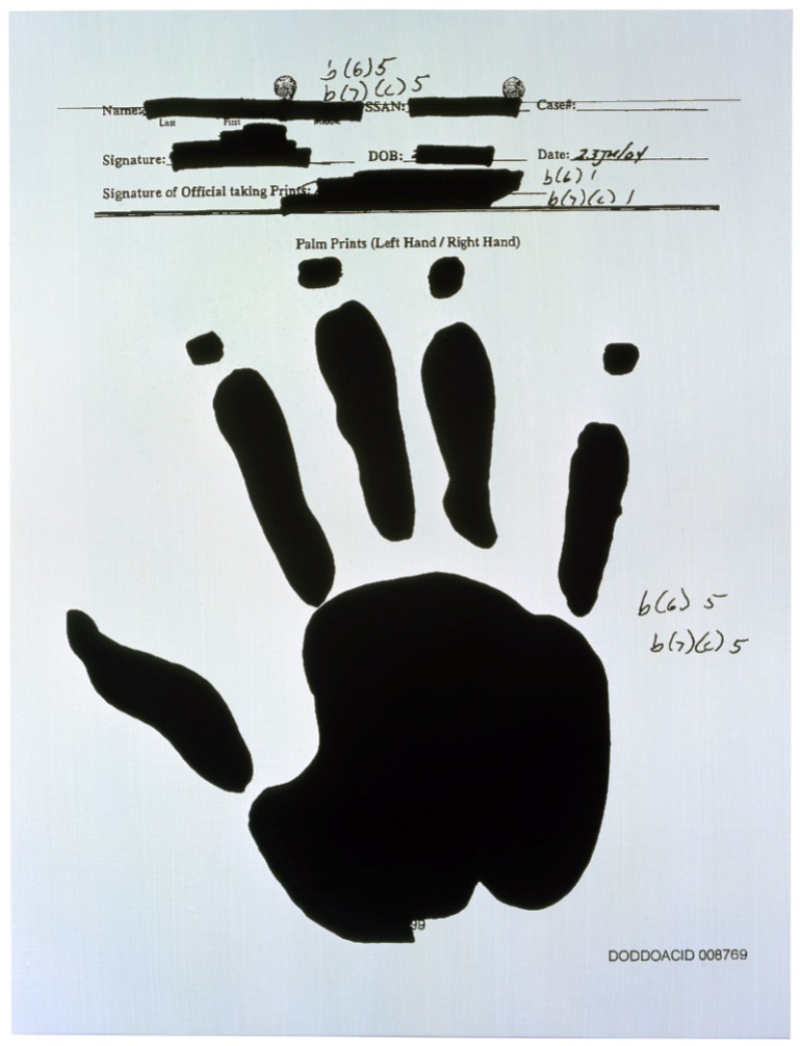

From December 2008 to January 2009, Operation Cast Lead destroyed around 15,000 buildings in Gaza, and killed approximately 1,400 Palestinians. The UN report on the Israeli assault, known as the Goldstone Report, is indicative of the decline of the witness. While the UN team carried out 188 interviews, much of the report is spent analysing the material traces of the war: the answer to the question of whether Israel’s attacks were proportional was sought in white phosphorous patches left on skin, and in the rubble of ruined buildings.

The speech of both Palestinians and Israelis was assumed—in the media if not in the report—to be biased and unreliable. Geospatial images of destroyed homes replaced Palestinian voices.

It’s not that people have somehow got less trustworthy over the last two decades; it is the political fora that have changed. In American politics, just as in polarised discussions over the occupied territories, speech is assumed to be a question of opinion and personal interest, and its reception is to be determined not by its content, but simply by where you stand when you speak: not so much the personal is political, as the reduction of politics to the personal. We each produce our own truth, and rest adrift in our weary solipsism.

V.

As the figure of the witness loses its power, new ways of capturing the earth become possible. Satellite images and computer models are called to the stand. In the border areas of Sudan where I work, George Clooney’s satellites keep dubious watch, witnessing from afar. The images will be sent back to forensic analysts in America, who will spend their nights searching for the tell-tale shape of a tank, or a group of tents that they will conclude is probably a military encampment.

In early 2013, I was in Washington DC, speaking at the State Department about the situation on the border. During a break, standing around clustered suits pumped with the latest developments from Mali, I spoke to a weapons expert, his PowerPoint slides crammed with photographs of small arms. He could read a bullet like a hieroglyph: the year it was made, the country of origin; then he would offer his interpretation — he told the history of the Sudanese border conflict as a history of guns and shrapnel, the details lodged in the surface of the earth.

Why, I asked him, is there such an interest in material history at the moment? They love this stuff, he told me, his arm encompassing the canteen of the State Department. It’s objective. What someone says. Ok. People say all sorts of things. You can’t argue with a bullet.

VI.

Linguistically, Weizman tells us, forensics derives from a technique of Roman rhetoric. The form consists in using objects to make an argument before a forum: prosopopoeia. Quintilian, in his Institutes of Oratory, clearly has high hopes, claiming that the form could “bring down the gods from heaven, evoke the dead, and give rise to cities and states.”

Who speaks for the gods today? If the Chinese bullets presented to the state department are signs, they index an arcane world inaccessible to all but a select few. All too often, the expert interpreting the object replaces an audience’s understanding of it. The rise in forensics seems part of Weber’s sad modern world, full of specialists and knowledge we can’t grasp, and a public willing to entrust questions of political and moral judgement to the happy hands of waiting technocrats, who will make neutral decisions based on the available evidence.

VII.